The Incubator

Awareness Day

National Storytelling Week takes place from 27 January to 4 February each year and is a celebration of the power of sharing stories.

To mark the occasion we share Julie’s birth story - told by Isobel James (Radio Times). Julie’s journey through neonatal care offers insights into the shock of giving birth prematurely, losing a baby and raising a child with a disability. Julie’s story connects, inspires and allows us to learn from her unique experience.

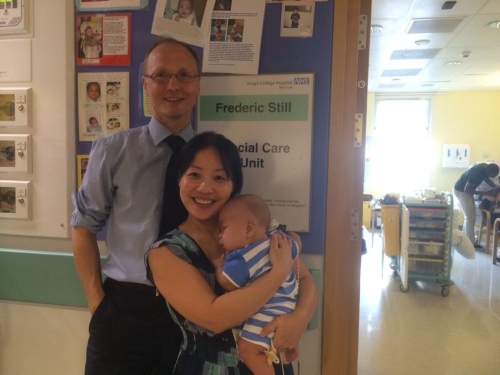

“When Julie started to experience stomach pain midway through her pregnancy it didn’t occur to her for a moment that they might be labour contractions. ‘It was way too early,’ she says. At just twenty four weeks, her twin babies were certainly on the edge of viable life, but within hours of experiencing that first twinge Julie had given birth. Instead of that precious first cuddle, however, her boys were immediately whisked away to be placed in special care, their lives hanging in the balance.

For Julie, 42, and her 50-year-old husband James life was turned upside down in an instant, transformed overnight from the usual hopes and dreams of any excited parent-to-be to one of incubators and feeding tubes as they willed their fragile baby sons to survive.

Prior to their sons’ birth, James and Julie, both solicitors, were nervous but excited about their impending arrivals. After relocating to the Midlands from London, where they met, they planned a country life for their family. ‘For most of my pregnancy there was nothing to suggest there might be a problem,’ Julie recalls. ‘We knew twins came with slightly higher risk, but I was healthy and well.’

Then, two days before Christmas, while visiting Julie’s parents in London, Julie experienced those severe stomach cramps. ‘I went to the A&E at Kings College Hospital when they got too painful at which point they said I was in advanced labour. We were just in complete shock,’ she says quietly. ‘We thought there was just no way the twins could survive.’

Yet they both did, initially. Jack came first, born breach and weighing just 724 grams. His brother Harry came fifteen minutes later, weighing 670 grams. Whisked away to intensive care, their parents were told they had only a ten percent chance of survival. ‘I remember walking through the neonatal unit with all the incubators and the noises of the machines to see them and there they were, so tiny, and dark, covered in bruises from the birth. It felt surreal; like it was happening to somebody else.’

It’s a common reaction, according to Dr Ann Hickey, lead clinician at King’s neonatal unit. She presides over up to forty babies, twenty of them in high dependency, and sees every day the bewilderment of new parents plunged into an often entirely unexpected nightmare.

‘For the parents of very premature babies one of the first conversations you have is that they may be here for six months or more and that’s very hard for them to understand,’ she says. ‘Most of them have had every expectation of normality in terms of the birth then the moment they come to us it’s utterly changed. They’re on a very different course, not just for the time they are here but in some cases forever.’

For James and Julie there was, at first, no looking ahead. Their babies’ struggles were gargantuan: Jack, their firstborn, had bleeding on the brain and required three life-saving operations within the first three weeks. Harry, meanwhile, was struggling to breathe. ‘All we could do was deal with what was happening hour by hour’ Julie recalls now. ‘It was bewildering, completely different to how we had pictured our life as new parents, but this was now our normal and we had to adapt.’

Yet tragedy lay ahead: by January 11th, the couple were taken aside by a consultant and told there was nothing more that could be done to help Harry with his breathing difficulties. ‘They said they could try and carry on but ultimately he wouldn’t improve,’ Julie recalls. ‘They were basically asking us what we wanted to do.’

As the parents battled with this heartbreaking decision, Harry started to deteriorate. ‘It felt like his way of telling us what to do,’ says Julie. ‘The one thing we both felt was that we didn’t want him to suffer.’

It is not an unusual dilemma in the neonatal unit, although Dr Hickey – a mother herself – fully understands the anguish of the parents. ‘Technology has improved but just because you can do something doesn’t mean you should,’ she says. ‘The care of any baby involves complex decision-making as a team based on UK standards but also our knowledge of outcomes. If it’s not in the interests of that baby to escalate care then we have that conversation with parents.’

For James and Julie, that meant agreeing to withdraw life support for Harry, who they cradled in their arms as he took his last breath. ‘We’d never had a cuddle with our babies until then so although they were his last hours it was incredibly special too,’ says Julie.

Amidst their heartbreak they were sustained by Jack, who was himself still only clinging to life. ‘I’m not religious but I’ve never prayed so much,’ says Julie. ‘It was touch and go for a long time.’

Yet Jack hung on and was discharged after eight months – the end of one journey and the beginning of another equally complex one for his parents.

Diagnosed blind at three months old, he was readmitted to hospital twice in the first few weeks with breathing problems, and while the outcome of the bleeding on his brain is not yet known he is likely to always require long term care.

Yet despite their traumatic journey Julie feels blessed. ‘It’s hard and exhausting but I wouldn’t change it for the world,’ she says. ‘Jack has so many special qualities. He’s taught us so much and brought so much joy. Caring for a baby with special needs is a different experience of motherhood, challenging but most rewarding’. “

After over 7 months in the NICU (Neonatal Intensive Care Unit), Jack was finally allowed home. Julie remembers their first night at home as wonderful, scary and extremely quiet.

‘Looking back, the first 2 years of Jack’s life, and especially the 14 months after discharge from NICU, has been the most anxious and stressful time of my life. When you are at home, with a baby that’s been tiny and sick for so long, reality kicks in.

As a mother and main carer for Jack, I felt so alone. He was not gaining weight. I was under pressure to get him to drink more milk and eat more solids. Yet, he had terrible reflux and was vomiting at least once or twice a day. This made me more stressed. I was counting calories and volumes every night. It was a vicious cycle that I didn’t know how to break. I felt I was at breaking point. There were times when I felt such a failure as a mother and questioned myself ‘Why can’t I get my baby to drink more?’ Your mind plays tricks with you.

You have no one by your side, who can understand what you are going through, who can help you.

My only source of support was from another mum, with whom I kept in contact via text messages. Our babies were in NICU together for 6 months. She, herself was also going through anxious times with her little boy. We supported each other with words of encouragement. Hung on to the fact that we were both going through the same difficulties with our babies. And told each other it will get better. She was my lifeline. My friend.

I don’t know how long this went on for. But I remember one particular day when I was feeding Jack, and he wasn’t eating very much, that I thought babies are like adults: some days they want to eat more, other days not so much. And this is OK. Also, I had to remind myself that this little baby has been through so much, that I should just let him be a baby and not rush things. I kept saying this to myself and eventually, the stress lessened.

So just before Jack’s 2nd birthday, I was finally told that he didn’t need oxygen anymore. So immediately we removed his tubes. It was a joyous moment to finally see his beautiful face without any tubes or sticky tapes. I then decided to reduce his reflux medications and then stopped them completely after a couple of months. It took a further few months before all his reflux symptoms disappeared and he was enjoying his food and gaining weight. This was the start of me taking control of things I can control and also just letting Jack be a baby, a little boy.

The anxiety is still there, but it doesn’t overtake my life anymore. I am just happy to be a mummy. The best job in the world.

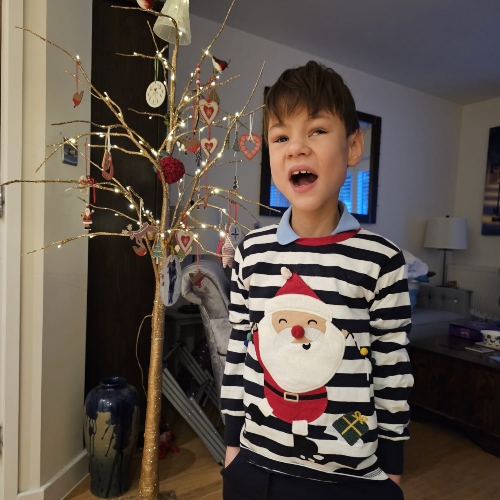

Jack recently celebrated his tenth birthday and goes to a special school for children with visual impairment. He loves it there and enjoys music, piano lessons, swimming and maths. He is thriving.

As Ickle Pickles’ Head of Peer Support, Julie now helps other parents going through neonatal care and hosts NICU coffee mornings at several London hospitals. Her honesty and compassion provide a source of comfort for parents facing similar challenges. She says “I don’t want parents to feel alone, like I did. I want them to know there is support out there if you open up.”

If you need help along your NICU journey, find a local event here and join us for a friendly chat and cuppa.

You can share your own story or experience with Ickle Pickles for others to read and take courage from.

.webp)

.jpg)

.webp)